18 November 2019

I’m naturally sceptical of the promises of new technologies. When the container technology was on the rise, for example, it took me a couple of years before I would fully embrace the technology. I rarely jumped into the bandwagon of innovators or early adopters. There’s a little part of me that favours stability. I felt many times that new technologies are just moving one problem from one place to another. Besides, why would I need new technology if what I know now is working?

When I first looked into the serverless architecture, I got a similar sheer of scepticism. Is serverless that kind of technology that will just move problems around and introduce new complexities? Given a tight deadline we were given by our client, we have decided to give serverless architecture a try. I have never looked back ever since as the benefit of the technology is real. Yes, there are problems that are moved around, but from the totality perspective, the technology brings an overall positive impact. My experience is analogous to the experience of other early adopters of serverless.

Working for a consultancy though brings me a wider perspective of what’s going on in the industry, which includes the sceptics of serverless. Hearing the stories from my colleagues make me feel like serverless is falling into the chasm. I’ve heard many stories of less successful serverless adoption and implementation. Organisations are stuck using serverless technologies only in the least risky part of their architecture.

What are the ingredients that we’re missing? How do we leverage what serverless technologies have to offer better? There is a paradigm shift in serverless. When there is a paradigm shift, we need to change the way we think about this new paradigm, so that technology can benefit more people in the industry, regardless of the organisation size. A set of principles will help you take the journey of this paradigm shift, and how you should approach the adoption of serverless.

When you are adopting a particular technology, you must have a good reason for the adoption. Most of the time technology is created to solve a problem, and understanding the problem that it has solved is crucial. Container technologies, for example, was solving the difficulty of reproducing software behaviour across different environments. Serverless technology is no different where there is a problem that it has managed to solve.

The problem that technology solves normally sits within a spectrum of technical to business problems. Many technologies out there have managed to solve technical problems, which would sit on the left-hand side of the spectrum. This is not to say that a particular technology is not solving any business problem, but the impact it makes to businesses are not immediately visible. Serverless though is sitting at the far right of the spectrum. There is a drive to its adoption as businesses get faster time to value. Serverless pay per use model might lower running cost, which might mean that the unutilised budget can be reinvested elsewhere. As the operational overhead of your system is significantly reduced, it might mean that development cost is reduced too.

If serverless technology is coming with all these positives outcomes, why then do we hear contradictory stories? There is always a trade-off in a decision we make, and there is a trade-off in utilising serverless. There are technical limitations to serverless, and vendor lock-in concerns still prevail. This is why the first important principle that you need to have is to focus on business outcome. Business outcomes must be at the forefront of your mind. The technical limitations, of course, shouldn’t be neglected but should be approached differently with the next set of principles outlined in this article. First, let’s address how this principle drive our thinking on lock-in concerns.

It is of course not easy to focus on business outcomes if you’re heavily concerned with vendor lock-in. The serverless services provided by every serverless platform are hugely different and not standardized. What if you are required to move to another cloud provider? Doesn’t that mean that the migration cost is going to be very expensive? How can one adopt something if they know that it’s going to cost them in the future?

Imagine that I’ve just lost my phone and about to buy a replacement phone, and I’m about to move from the UK to France. I know that the new phone charger only works in the UK. Should I still purchase my replacement phone? I would, because the phone is what I need, I can always replace the charger later. That would also mean that the UK charger I’ve got wouldn’t work if I move to France and I would have to purchase a new one. Does that mean that my purchase would cost more? Yes, it will, but it will also mean that I can make use of the phone before my move. Besides, I could always get a new France compatible charger later. Better yet, I can just buy a travel adapter that will convert my UK plug to France plug. These lightweight travel adapters are also normally the best ones as it will not attempt to abstract every country’s possible plugs; shamefully most adapter that supports multiple countries I’d bought is always broken fairly quickly!

When you think about migration to other cloud providers, think about the probability of the migration from happening, just like my imaginary move to France. If there is a solid requirement that you will have to migrate to another cloud in 1 month, for example, then probably you should start your development in the new cloud provider anyway rather than debating whether the migration cost is going to be expensive. Just like the imaginary phone I purchase, you should be getting your development moving instead, because otherwise, you’ll suffer from opportunity costs.

Opportunity gain should be part of the totality that you’re looking into. What we are worried in vendor lock-in, is normally the high cost of migration. It is a fact that the migration cost will not be zero here, as compared to other architectural styles. Opportunity gain should be calculated as part of your cost calculation, which means your total lock-in cost might even be negative. You should attempt to maximise your opportunity gains and minimise your migration cost. I have written a separated article to mitigate the serverless lock-in fears, you can find it here.

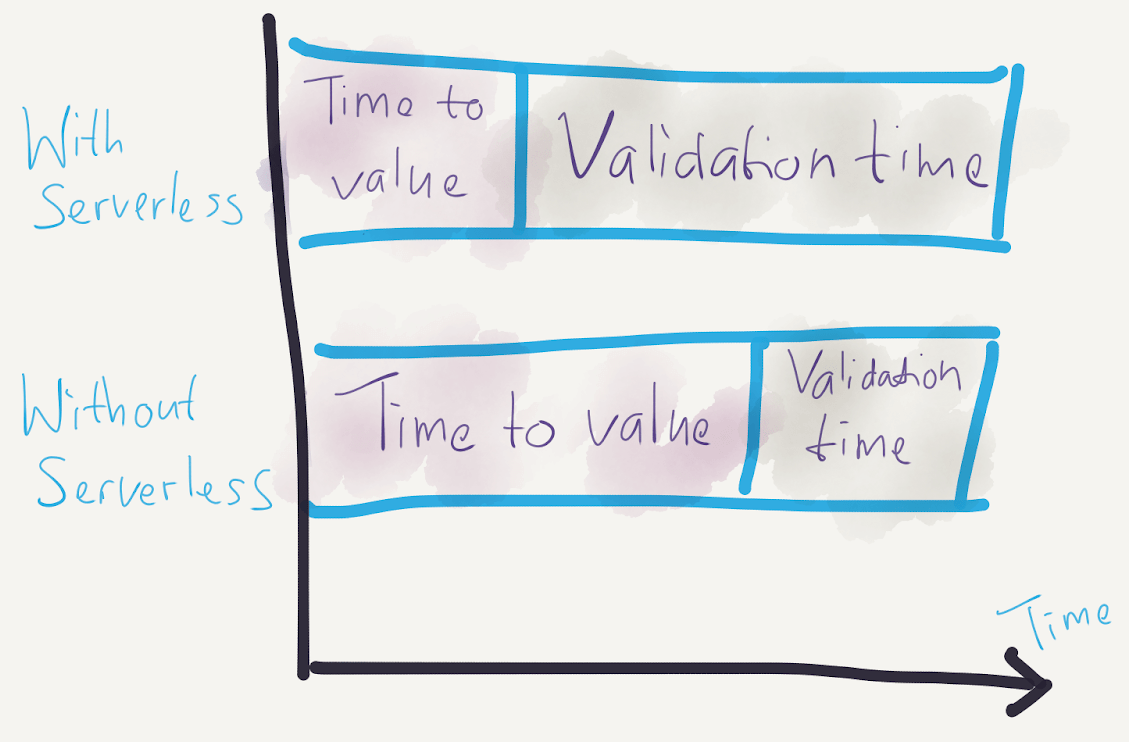

Moving away from the negative aspect of serverless, I think it is worth covering and reemphasizing what business outcome serverless is bringing to the table. One of the well-known benefits of serverless is how you can deliver value faster to your customers. You are getting a faster time to value, which means that it’s going to take a less amount of time for you to deliver values, iteratively, to your customers. Faster time to value would also mean that you’ll get to validate your idea quicker. Especially in a competitive market, getting to a point where you can learn from your customers quickly is invaluable.

Should serverless architecture than just be used for prototyping? A combination of faster time to value and technical limitations seems to indicate that we’re building a prototype. There are many types of prototyping, but the traits of serverless architecture have eliminated some of the downsides of prototyping that I wouldn’t consider the application as a prototype anymore. Solutions built on serverless architecture is not a prototype, and we should avoid the word deliberately. When people hear about a prototype, people would think about a quick and dirty throwaway code or something that will not scale. Elasticity, for example, is one of the traits of serverless architecture, hence serverless architecture is not falling under the category of a prototype that will not scale. Many technologists have found my other article to be very useful, especially in understanding the pros and cons of what the traits of serverless architecture brings, you may find the article here.

The elasticity of serverless architecture is not only aiding your technical solution but also your business. Elasticity makes the time for you to validate your solution longer, and there are at least two reasons for that. Firstly, when a product is struggling when the solution shows unexpected demand, the serverless architecture will be able to handle the load better by default. Secondly, when a product is showing less demand than expected, the business won’t have to pay for huge infrastructure cost. As the time for you to validate your solution is living longer, you are also getting a level of flexibility to reprioritise your requirements. Your business is seemingly gaining elasticity too due to serverless architecture.

The following picture therefore should summarise the outcome serverless is bringing to businesses.

The second principle that you need to have is to leverage commodities first. When a subject is deemed as a commodity, that subject has been commercialised widely so that it is very easy for it to be consumed by anyone. A commodity is those apples that you can purchase from grocery stores or a guitar that you can grab in any musical instrument stores. Electricity is one other good example of a commodity. As a daily consumer of electricity, many of us wouldn’t know how electricity is it being provided to us. The only interface you would be exposed to is just electrical sockets in your house, and many of us wouldn’t understand what’s happening behind the socket.

Serverless technology is a commodity. When you are adopting the serverless architecture, you wouldn’t need to know how things work behind the curtain. The significant operational aspect of your infrastructure is commoditised.

Imagine for a moment when you’re trying to buy a newly built house and you realize that the house requires its own electric generator. There are no portable electric generators that you can buy too. Essentially there are no commodities available in the market at all. What’s being provided to you, is a set of instructions on how you can build your own electric generator. You would also need to hire experts to build and maintain them if you don’t have the necessary skills. Now you’re having a completely new kind of problems, just because you need to find somewhere to live. Wouldn’t it be nice to have something that just works without your interference?

The adoption of serverless architecture is coming from the same idea. The only thing that you’re exposed to is an interface provided by a serverless platform. When you’re utilising Backend as a Service, or BaaS, your electrical socket is the SDK or the console. For example in AWS S3, you are just calling putObject operation to store a blob, you wouldn’t know how and where your blob is being stored. They have been commoditized for you.

This is how you should perceive serverless architecture, you should have the preference to leverage them first.

There are two ways organisations approach the adoption of serverless technologies:

Build on non-serverless architecture, then migrate to serverless architecture

Build on serverless architecture, then migrate to non-serverless architecture

I’ve seen many organisations approaching the adoption with the first option, and I believe this is the wrong order of iteration. If we embrace the idea of leveraging commodities first, then the order of your iteration is really important.

The order of iteration that you should take is similar to a purchase made in any commoditized industry. Let’s have a look into the order of iteration on how I purchased an electric guitar. As a fan of The Muse, their music made me interested to master electric guitar. My first instinct is to get the guitar the band is using. Shockingly, I discovered that it’s a custom made guitar which costs up to 40 times more than other decent guitars and takes up to 12 months for it to be built. Rather than waiting for 12 months to get my guitar, I could purchase a cheaper guitar from a musical instruments store right away and start learning. This cheaper guitar wouldn’t have a like for like feature with the custom made ones, but I discovered that it’s good enough to get me going. As a matter of fact, I learnt that I’m not so good at guitars, I’m so glad I didn’t naively order that custom-built guitar.

To have this preferred order of iteration, the quality of the commodity must be good enough. We prefer to buy vegetables from grocery stores than growing our own vegetables because the vegetables that can be bought are good enough. If the quality of the vegetables is consistently rotten everywhere, you would probably start to consider to grow it on your own. In my experience, the quality of the serverless platform is good that we can iterate in this preferred order.

A serverless platform is the key enabler which provides the services that you need to build a serverless architecture in. The principle of leveraging commodities first should be applied when choosing a serverless platform too. There are two main approaches to choose a serverless platform here: use a cloud platform or build your own platform. Understanding the principle well, the cloud platform is what you should consider as a commodity, hence what you should prefer to use.

You have to have a mature serverless platform to enable delivery teams to build serverless architecture. There are many custom-built serverless platforms readily available out there, like Kubeless for example, but the operational aspects of your solution will not be fully commoditized. Not only you are going to need the expertise to set it up, but you would also need the time to set it up too. If you are using the public cloud, you can start to build your solution today.

When you are trying to spin up a custom-built platform, your objective is to create an equivalent level quality of service that your cloud is providing. Trying to match your cloud provider’s operational experience in providing a service is very expensive. In terms of return of investment, what they are building have been battle-hardened by many of their customers. If you are trying to build a self-managed platform, you will have to go through the same cycle and the Total Cost of Ownership will be very expensive. If you are not on the cloud, I highly suggest you to rethink about your motivation to adopt a serverless architecture. Of course, you might have various requirements that might prevent you from going to the cloud, they will not be discussed in depth here.

If your enterprise is big enough, you might argue that you will have the capacity to build up your current platform. But is it worth the cost? If you have your own data centre, would you have your own electric generator? You might say yes, but most of the times your own electric generator is a backup, in case the main electric generator is not working. It’s quite rare for it to be used as the main electric generator.

Take your journey of adopting serverless in the cloud as a learning process. Once your solution is maturing in the public cloud, you would understand better about what serverless really means in your organisation. You then discover what you need and what you are missing, then take it as learning should you decide that you want to start having your own custom-built platform. Although, I should mention that there is one caveat with a custom-built serverless platform. Serverless architecture is typically built on top of FaaS and BaaS. At the moment, my observations around what’s going on in the custom-built platform is the lack of BaaS. So make sure that you cater for the cost of building your required BaaS if you go down the custom-built route. For example, if a team needs something of an equivalent of AWS S3, what kind of service would you provide to enable teams to adopt serverless architecture?

Sunk cost fallacy, is perhaps one of the biggest problems of taking the wrong order of iteration in a commoditized industry. Should you start with a custom-built serverless platform first, you will have a higher tendency to keep it, and continue to make your future decisions based on the amount of time and money that you have poured into the platform. As briefly outlined above, the cost of creating a platform in your organisation is not trivial, hence you will have a high sunk cost here. This is similar to how decades ago when using clouds is still a niche. Organisations who have heavily invested in building their own data centres would mostly make their decisions based on the data centre that they have.

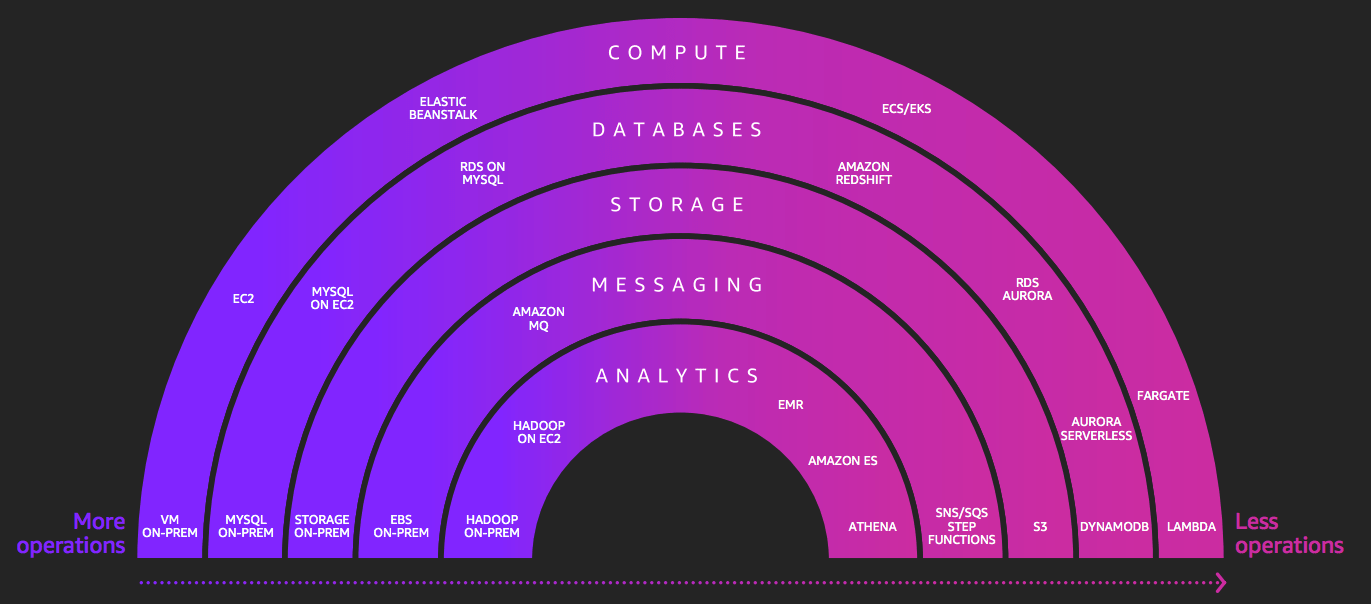

Given a cloud platform, there are many services that it offers for you to choose. When we talked about leveraging commodities first, how do we make sure that the services we leverage are the right ones? Unfortunately the word serverless is often bloated with other marketing meanings, which means you might accidentally pick non-commoditizing services that the platform provides, even when they’re advertised as serverless.

Guardrailing your options here will reduce such error. Decision-making process can be an expensive process. When you are driving to your destination, taking the highway route would be faster than the smaller roads. It’s faster to take the highway because it provides fewer options along its way, which in turn will let everyone drive faster to reach the same destination. You need to be explicit about the options teams can use.

AWS has provided the Serverless Spectrum diagram that helps you understand what kind of services which are considered 100% serverless (in the context of this article, serverless means 100% serverless services). You should choose only the services which fall on the far right here from the AWS serverless spectrum, first. These examples are Athena, SNS, SQS, Step Functions, S3, DynamoDB, Lambda.

Serverless

Spectrum from 2018 AWS re:Invent

Serverless

Spectrum from 2018 AWS re:Invent

By putting a guardrail around your options, you are also forcing the emergence of patterns. Patterns can and should be tackled from an organizational level by creating a paved road. When everyone is facing the same problems in an organization, a pattern will emerge, and eventually, you will discover that you can start to find a shared common solution. For example, you will discover that you might need to have a good SMS alerting system to support your products. If your current platform doesn’t support this, you can start to look at third-party SaaS, like PagerDuty, and make sure that it becomes an integrated part of your serverless platform.

The way you treat SaaS should be fairly similar here, it’s about using the commodities first and you shouldn’t be limited to your cloud platform. SaaS falls under the definition of commodities, especially if they’re integrate-able to your existing cloud-based serverless platform. Learn from what they have built, and then iterate to a custom-built version of it if you really need to.

So far, as per what I have outlined above, you should design your solution with a cloud-based serverless platform, with constrained serverless services first. You might have a couple of concerns here, especially if you have experienced building serverless architecture before. Where should I store my data? With its technical limitations, Will DynamoDB be able to satisfy my requirements? Most of those services are not built on a standard protocol, what about vendor lock-in?

The mindset shift that you need to have is to acknowledge that you’ll always be faced with limitations when a commodity is used, and you have to be able to embrace its benefits more than its limitations. This is why the principle to embrace the fundamental shifts is really important. A commodity is something that would normally be developed to target a mass market, hence one of its other property is a set of limitations because you can’t satisfy everyone’s needs by being generic. Yes, there will be limitations, but I believe that faster time to value will outweigh the technical limitations (see the focus on business outcome principle for more on this). These serverless services are the new fundamentals, and you have to learn to embrace it.

Embracing new fundamentals, of course, is not easy if you’re faced with technical limitations. In the following sections, I outline approaches on how you should perceive the the new fundamentals, and how to deal with the technical limitations.

In any software architecture styles, there will always be fundamentals that are associated with it. These fundamentals are the knowledge that you are expected to know and become familiar with when you’re working on that software. If you’re working on a Java application, you are expected to know how to use a HashMap. If you’re deploying to a Linux filesystem, you are also expected to know how to navigate in the Linux filesystem. These fundamentals are something that is rarely discussed because technologists are expected to know them.

One neglect you might have when adopting serverless is the realisation that there are fundamental shifts in a serverless architecture. One of the main fundamental shifts is the usage of BaaS that a platform provides. For example, if you’re trying to store data in AWS, you have to acknowledge that AWS DynamoDB and S3 are the new fundamentals. Failure to recognise this, there will be a lot of time-consuming debates.

Some approaches that teams might take might not be applicable anymore if they don’t embrace these new fundamentals. For example, it’s a known approach for teams to iterate with a simpler solution first, such as by utilising HashMap or file systems to store their data. As FaaS is inherently stateless, you wouldn’t be able to utilise HashMaps nor filesystems. How then can you embrace the idea of validating your solution with simple solutions? One way to think of this fundamental shift is, S3 is your new file system, DynamoDB is your new in-memory hash, and SQS is your new in-memory queue. You should be able to use these services without hesitation.

These new fundamentals, the serverless services, have similar characteristics to a filesystem or HashMap. They normally have a lower learning curve than the solution perfectly chosen for a particular use case. They will also not scale, as compared to the perfectly chosen solution; to state that serverless architecture will not scale of course is a huge understatement.

The word database is a big word. Typically in a big enterprise setting, when you’re choosing a database, you’ll be down in a hunt for the perfect database, and someone would be monitoring closely to what database you have chosen. It is unfortunate for DynamoDB to have a suffix of “DB”. There are a lot of characteristics from DynamoDB that make it feel a lot less like a traditional database. Deleting gigabytes of data from a table, for example, is near-instantaneous, just like how you are shutting down an application process and how they freed up your RAM.

When the fundamentals are shifting, they’re the new normal. You shouldn’t be shocked if a house has electrical sockets. On the contrary, you should be shocked when a house doesn’t have any electrical sockets. It’s the norm.

Once you adopt serverless services, you will eventually hit their technical limitations. There are two types of technical limitations, soft limits and hard limits. I will be discussing on how you can deal with these limits independently in the next sections.

Soft limits are the technical limitations that can be overcome. Cold start, is one of the soft limits of serverless architecture. Due to a cold start, the request to your FaaS for the first time may be inconsistently slow, due to the fact that there’s an ephemeral compute being spun up behind the scene. Execution time limits is another soft limit that you have in FaaS, whereby an AWS Lambda can only run for a maximum of 15 minutes. There are tricks that you can do to create a workaround for the soft limits, you can duct-tape them. Duct-taping these soft limits should be preferred because the last thing you want to do is to drop the many benefits of serverless architecture.

Duct-taping techniques have been developed to overcome many serverless soft limits out there. For example, the community has gained a better understanding of the internal behaviour that affects AWS Lambda’s cold start, and started to develop tools to keep them warm. Isn’t duct-taping hacky, though? Why would we adopt these duct-tapes? Yes, duct-taping is hacky, but remember that having some limits is the nature of commodities. concept.

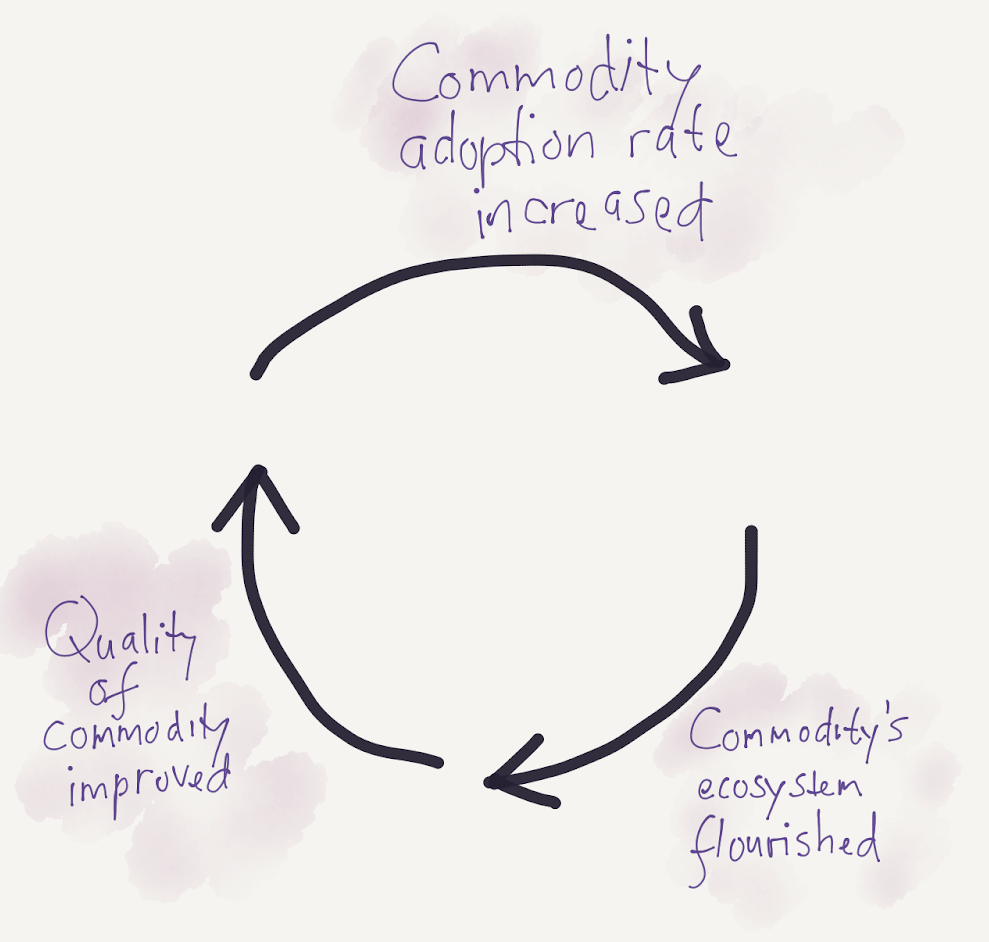

I believe that many of these duct-tapes are temporary because well-sought commodities will improve over time, and eventually the duct-tapes wouldn’t be necessary anymore. There are many soft limits in smartphones when they were first popularised. One of them is their short-lived battery. Many started to develop duct-taping techniques to overcome this battery problem. People started to find ways to charge the phone faster, and third party applications were developed to mitigate this problem. The ecosystem around this problem flourished too, including the popularity of battery packs. Years later, smartphones have better built-in batteries and better Operating Systems.

A well-sought commodity will form a virtuous cycle that will improve upon itself:

A serverless platform is falling into the category of well-sought commodity, and the virtuous cycle has alleviated some of the soft limits a number of times. Especially in the software industry, the virtuous cycle can move a lot faster than other type of commodities. Execution time limits used to be a technical limitation for many in the past. The time limit of AWS Lambda has been changed from 1 minute to 5 minutes, then now 15 minutes to satisfy more use cases. Before the time limit was increased to 15 minutes, many technologists were duct-taping this limitation, and the duct-tapes now are no longer necessary for them. Azure Functions premium plan promises to eliminate the cold start issues. Workarounds on long-lived connectivity are disappearing as AWS API Gateway now supports WebSockets.

Serverless architecture also has hard limits, which are the limits that you can’t overcome. One of the well-known ones is its high latency and many organisations are not adopting the architecture due to this problem. For example in AWS, the high latencies can be introduced from the hops through the client, API Gateway, and Lambda. It can also be coming from calls to S3 or DynamoDB.

These hard limits, of course, can be forcefully duct-taped too. There are various caching techniques for example, but they wouldn’t solve the underlying high latencies, and sometimes even caching can’t be used if it doesn’t fit your use case. If none of the workarounds is satisfactory for you, unfortunately, you have hit the limits of serverless architecture, and maybe it’s not the right fit at all for your need. For example, if you know that you are required to handle 6 million transactions per second, you would probably need to have a look into Disruptor, not serverless architecture. That said, I’d like to think that it’s more common in the software development world to have uncertain requirements. You won’t know if you are going to need to handle 6 million transactions per second until you have learnt enough from your customers. Reduce your time to value, and learn if whatever you’re building has the right market fit.

When you are faced with hard limits, I encourage that you first validate if the hard limit is going to affect your product feature. I’d been in multiple discussions where the business would like to get a response in real-time, and later discover that the definition of real-time is not 10ms and the higher latency of serverless architecture in the end wasn’t a problem for us. Validating if your hard limits are really a hard limit are important too. Many of the technical limitations in serverless architecture are mistakenly seen as hard limits when they’re actually soft limits. One example of this is the cold start issue in FaaS, as discussed in the previous section.

When you have learnt enough that you are actually constraints by the hard limits. My advice when this happen to extract the proven expensive parts, which is the principle that will be covered next.

When you are faced with hard limits, the last thing that you want to do is to redesign your entire architecture. Don’t mark your architecture as a legacy, because what you have delivered here is not a prototype. When you don’t like the apples sold in your nearest grocery store, you don’t suddenly grow all of your vegetables on your own, right? In this section, I encourage you to extract the proven expensive parts, and what I mean by it. When this principle is applied successfully, the majority of the components in your architecture will still be serverless, and the extracted part maybe non-serverless.

Let’s dissect each of the words in the principle.

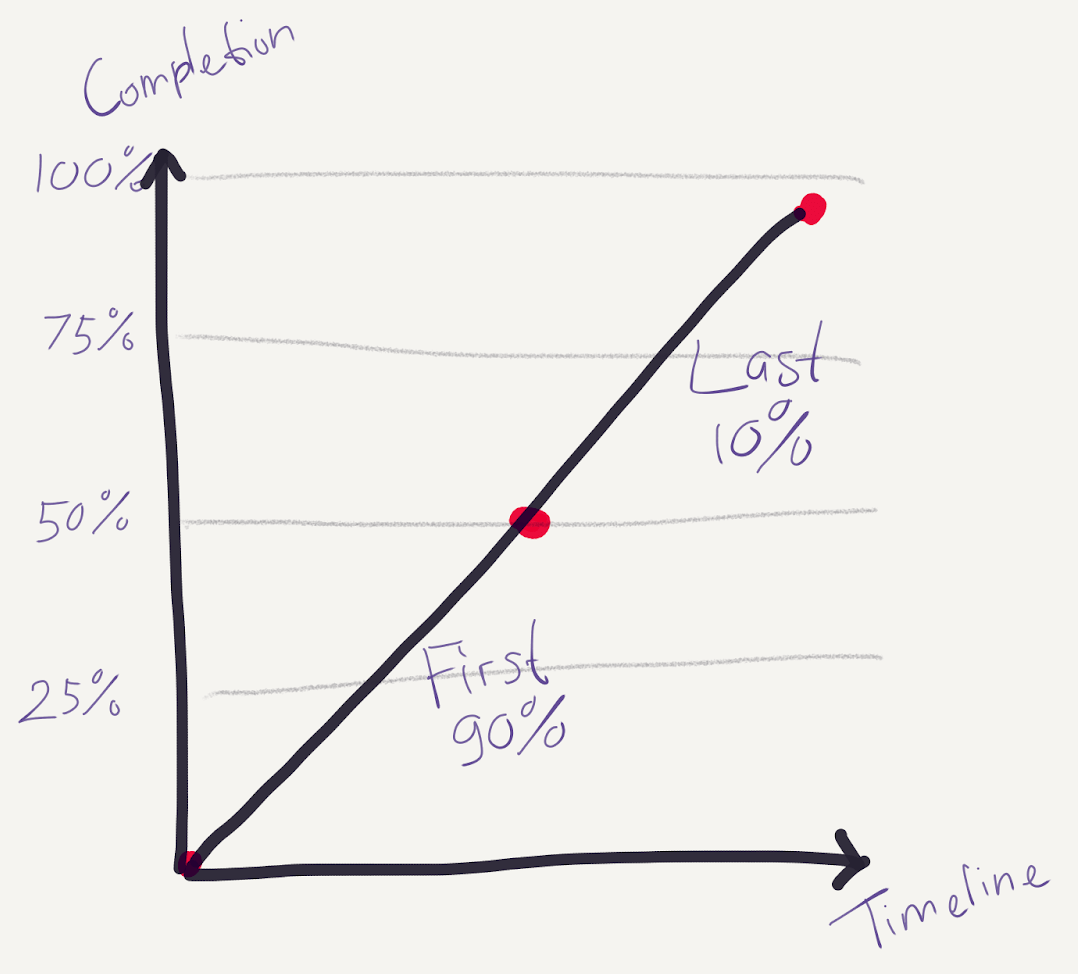

Working around your technical limitations can get expensive over time. Either your solution is getting expensive to change, or expensive to run, either of them are falling into this category.

As previously described, there are always limitations from a commodity. Introducing duct-tapes to your solution might get costlier over time, and trying to overcome the technical limitations may get expensive. This is similar to the idea that you should watch out for the last 10% trap:

Although it can get more expensive over time, it’s worth reiterating that over time the ecosystem around the commodity will grow as well. Libraries, patterns, and frameworks will grow, and duct-tapes would be cheap to be purchased too, as per described before.

You are encouraged to track the running cost of your architecture and don’t assume that the cost will be low. You can introduce a fitness function for its run cost too. SaaS, which is preferable when your cloud provider doesn’t provide the service you need, can be costly too depending on its pricing tier. When there is growth, for example, in your company, you might suddenly fall into a different tier. So you have to make sure that SaaS usages are tracked too.

If you have the sense of which part is expensive to change or run, the next step is to prove that they are really expensive. Proving the expensiveness is important, as our intuition is often misleading.

Even though your running can get costly, you always have to look into the Total Cost of Ownership. One cost that is commonly overlooked is the development cost of a custom-built platform, which would include a chain of recruitment, cultivation, salary, etc. In oversimplified calculation, if you’re paying £10000 per month for a contractor (£500 per day), a cloud running cost of £10000 per month is not a huge amount if you’re looking into the total cost. Total Cost of Ownership, of course, is difficult to prove and measure, but any attempt to measure here is better than nothing.

If you fully embrace serverless architecture, you will discover that your deployment units are smaller than usual. This means the individual parts of your architecture must be able to be extracted easily, and you should extract only the part that you have proven to be expensive.

An example would help to illustrate this. We discovered a need to integrate Kafka and AWS Lambda. As there is no integration provided in the platform yet, we have decided to have a continuously running Lambda to poll from Kafka. This Lambda, unfortunately, is consuming 80% of our cloud bill. Due to this expensive cloud bill, we were asked to spin up our own Kubernetes cluster and move our entire architecture there. Even though this sounds appealing from cloud bill perspective, there are many aspects of architecture that we needed to consider. Should we just extract the expensive part out, we would pull the Kafka polling component out, and leave the rest in the existing serverless architecture.

Given you have proven that there’s an expensive part, it’s now the time for you to extract it out. This may mean that you’ll be extracting the expensive part out to container technology, like AWS Fargate. Architecture or design principles is the key to having the ability to extract only the expensive part. There are many times where design is neglected in serverless architecture, and the argument “these are just functions” have been used, which is untrue.

When you design your architecture well, you help reduce the cost of the component extraction. This means design principle like SOLID would still apply in a serverless architecture. One example here is to make sure that the delivery mechanism of your component is separated from its main logic. This includes the delivery mechanism of when your function is triggered and the delivery mechanism of when you are talking to other components.

It’s been a long read, so let’s take a step back to recap what you have read. To ensure that you’re unlocking the full potential of serverless, a mindset shift is essential. Having a strong set of principles is helpful to have this mindset shift, in an organisation of any size. There are four principles that I’ve discussed in depth in this article:

Even though I’ve framed these principles as to how you can adopt and implement serverless technologies, I believe you can view these principles to help you develop a product faster to the market regardless of whether you’re currently looking into serverless or not.

My thanks to Seema Satish and Kief Morris for reading and giving feedback on the initial version of this article. To Martin Fowler who has provided many feedback that leads me to restructure this article for the better.